We grew up with a reverence for the Zik.

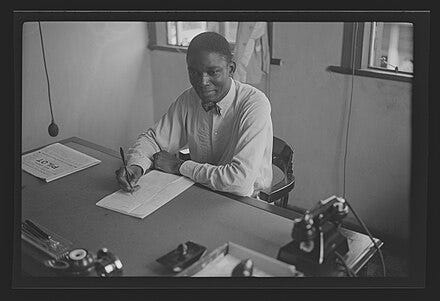

There's no child who lived in Southern Nigeria in the early 2000s who didn't love Azikiwe. We were schooled in his lore —in the stories of his birth in Zungeru, present-day Niger State (in Northern Nigeria), to his academic foray to the United States and his messianic return to lead Nigeria's nationalist struggle and become our first President.

He was the perfect role model.

Nnamdi Azikiwe was an intellectual beast who we never met (he died in 1996) but we imagined as warm and affable. To us, he was the Zeus of the Nigerian pantheon; premier of that historical council of Nigerians who sacrificed dearly for and won us our precious political freedom from the British.

He was the iroko in our forest of trees.

Growing up in Nigeria is an exercise in disillusionment. First, the Zik disappeared from our lives.

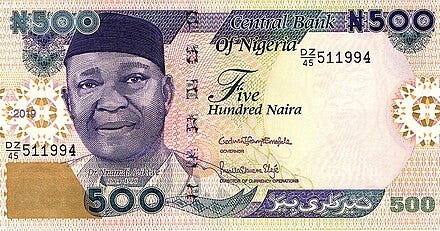

As we graduated past Primary School, he was barely ever mentioned again (in school or on television). Azikiwe was only frozen on 500 naira notes and in those charts showing a roster of Nigeria's Presidents. Always first in line, his smiling, cheeky portrait sat before rows of mostly despotic military leaders we were taught to treat with contempt. And that has been all.

This is why I say ours is a nation of dead gods.

American politicians frequently invoke past leaders because the people believe in them. They call on the spirits of the men who epitomize the creeds of their nation.

There is Benjamin Franklin and his fellow drafters of the "American Bible", the Declaration of Independence.

There is Abe Lincoln and JFK for the ideals of the Republic.

What about Martin Luther King Jr. and co., for civil rights?

Such is the American penchant for heroes in society and culture that they have even invented whole fictional universes of cape-toting superheroes.

They understand that people need something to believe in. And then they need exemplars to embody those values. In the midst of the storms of nation-building, the people can look at them, these idols, and see the paradise they desire. Like St. Peter fixing his eyes on our Lord, mere men can walk on water.

Such is the unbridled power of faith in shared values.

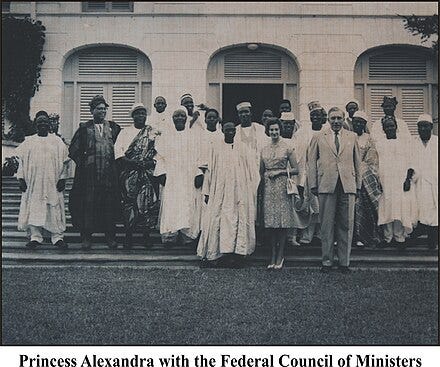

The Zik and his host are more than mere historical politicians. They represent some of our finest great values: an unrelenting, fighting spirit; the power of intellectualism; the salvation of a people.

They are like Moses.

They are the gods of a nationalistic religion.

Why have we killed them?

Zik and his pantheon have been sucked into the whirlpool of other "Nigerian leaders". They have been buried in the cacophony of criticism that is perpetually hurled at this latter elite for their ongoing and shameful legacy of governmental pillage.

Even worse, there have been attempts to "expose" Azikiwe. To unmask "the truth" behind his struggle or to just dampen his glowing reputation.

We were young when we started hearing narratives of how Nigerian nationalism wasn't a noble crusade steered by knights in shining armour. Rather, that it was a kitchen committee of politicians only intent on dominating the nascent nation or carving out spheres of influence to satisfy their lust for power and wealth. Loyal only to tribe, class and creed, Independence (and the vision of one Nigeria united in love) was a snake oil scam.

Little wonder, the critics say, that the young republic tripped almost as soon as she was born. We fought a largely ethnic-based civil war in less than a decade of independence and the scars are still bared. Five more decades down the line, Nigeria is a slumbering giant and the Zik's successors are counted as some of the most corrupt regimes in contemporary world history.

I could discuss Dr. Azikiwe's sterling contributions to the birth of Nigeria as an independent political entity but it would feel like lazily glossing over better volumes that have been penned about him and his comrades.

This essay is more than a seeming glorification of a man's activism. Or a deification of his person.

I am saying we have killed our prophets.

When a people have nothing to look forward to, nothing to believe in, when they have no more hope for salvation, the nation eats itself from the inside.

We have forgotten the very foundational creeds of our nation, even chipped away at them. And we can build nothing lasting over these ruins.

Unlike my peers and I, the Nigerian child of today isn't growing up into disillusionment. He is growing up in deep distrust of our systems, starved of national pride. Today’s Nigerian child is like Man, when he was naked and pummeled by the Elements.

This was before he either concocted the comfort of weather gods or they appeared to him.

At this time, Man was painfully aware of difficulty and there was no succour.

This is the way we are now. All around us is in decay.

The educational system is in a rot. The power sector is weak. Healthcare is ill. We are the poverty capital of the world. And any wistful recollections of "the good old days" which may have shoved us forward, are buried alongside our gods.

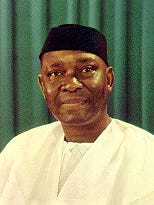

The Zik is one of the most potent symbols of African self-determination and it is necessary that we re-institute the veneration of national idols like him.

He may not have been perfect and we cannot name any two men who were, but nationalism is a form of religion that crumbles without belief. The youth need, as much as they do employment and opportunities, idols to aspire towards. And without history, any national project is doomed to fail.

The death of the Zik in our social psyche, his slow erasure from our active collective memory is not just a consequence of (recent) callousness in the cultivation of national pride but a symptom of a withering national image and identity. A symptom of a dying nation.

In bleak times like these, men like the Zik can be lighthouses, reminding us of the "labours of our heroes past" and illuminating the path to the future we deserve.

Let us resurrect the Zik of Africa.

You are not wrong that people need something to believe in. However, I cannot deny that I have reservations about 'our heroes past'. All of 'em.